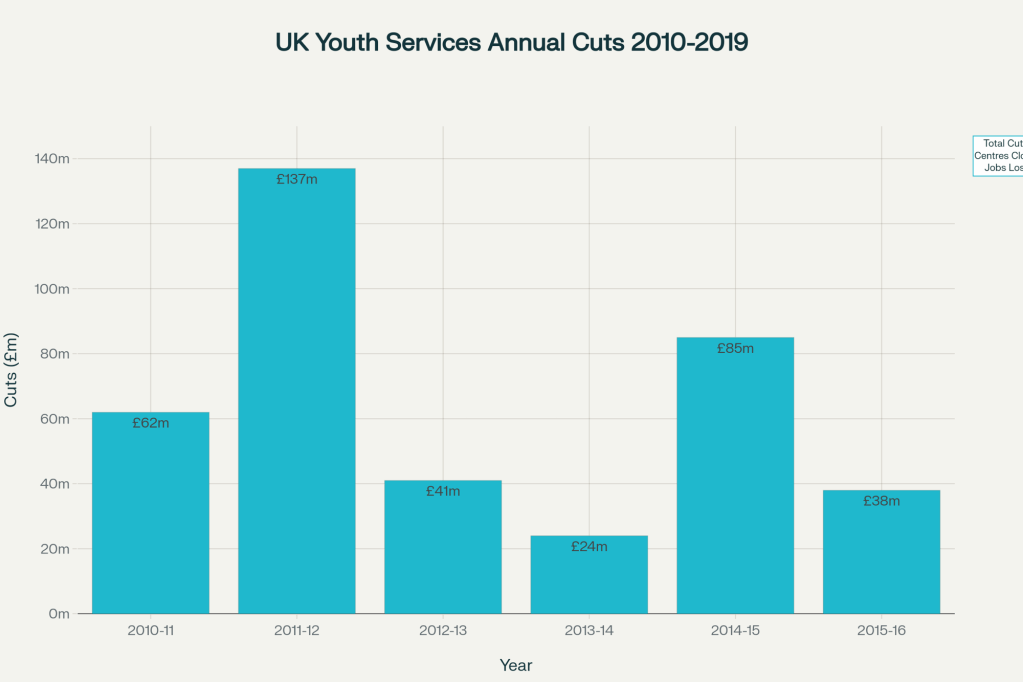

The devastating impact of austerity on youth services across the UK since 2010 represents one of the most short-sighted policy decisions of our time. With over £400 million cut from youth service budgets, more than 1,243 youth centres closed, and 4,500 youth worker jobs lost, we have witnessed the systematic dismantling of the preventive infrastructure that kept young people safe and engaged in their communities. In Liverpool, as across the nation, we have seen the consequences of this ideological vandalism play out in our neighbourhoods through rising antisocial behaviour, increased youth involvement in serious violence, and a generation of young people left without the support they desperately need.

As Cabinet Member for Health, Wellbeing and Culture in Liverpool, I have witnessed firsthand how these cuts have created a perfect storm of challenges for young people in our city. However, I also see tremendous opportunity in our innovative approach to using public health funding to rebuild youth services from the ground up, creating a more integrated, evidence-based system that tackles the root causes of poor outcomes for young people while delivering better value for money and measurable health improvements.

The statistics paint a stark picture. Research by UNISON reveals that between 2010 and 2023, England and Wales lost two-thirds of their council-run youth centres. In Liverpool specifically, we experienced some of the most severe cuts during the Lib Dem and Tory Government years, with the city forced to reduce youth service spending by more than £2 million in the 2014/15 financial year alone. This was part of a wider pattern of disproportionate cuts to areas with the highest levels of deprivation – Liverpool City Council faced cuts of 27.1% while the least deprived area in the country, Hart District Council in Hampshire, faced cuts of just 1.5%.

The consequences of these cuts have been profound and predictable. Liverpool has seen knife crime reach its highest levels in a decade, with Merseyside Police recording 945 serious crimes involving knives in the most recent year – an 18% increase. Anti-social behaviour has also risen, with 8,524 incidents recorded in Liverpool in the most recent data, representing a rate of 16.7 per 1,000 residents.

More concerning still is the 7.6% year-on-year increase in antisocial behaviour incidents between 2024-2025, suggesting that despite our best efforts, the underlying issues that drive young people toward problematic behaviours remain unaddressed. Youth workers consistently report that 91% believe cuts have particularly impacted young people from poorer backgrounds, with increases in mental health issues (77%), substance abuse (70%), and crime and antisocial behaviour (83%).

So why is this of any interest to Public Health, and why should we utilise the Public Health grant to address this issue?

The traditional view of youth services as purely recreational or social provision fundamentally misunderstands their role as powerful public health interventions. Youth work operates at the intersection of multiple determinants of health, addressing risk factors that drive not only antisocial behaviour but also mental health problems, substance abuse, educational underachievement, and long-term social exclusion.

Research consistently demonstrates that youth work delivers significant health outcomes. The government’s own Youth Evidence Base research, published in 2024, found that young people who received youth work support as teenagers were happier, healthier, wealthier and more active in their communities as adults. The study revealed that youth work has positive effects lasting well into adulthood, with participants showing better employment prospects, improved mental health outcomes, and reduced involvement in criminal activity.

This makes youth services a natural fit for public health funding, particularly given that the Public Health Outcomes Framework already includes indicators covering violence prevention, mental health and wellbeing, and community safety. The ring-fenced public health grant, worth £3.884 billion nationally in 2025-26, provides local authorities with the flexibility to invest in interventions that deliver measurable public health outcomes – and youth services, properly designed and delivered, represent exactly this type of intervention.

Liverpool’s Innovation: A Public Health Approach to Youth Services

In Liverpool, we are pioneering a new approach that treats youth services as integral public health interventions rather than optional add-ons to statutory provision. This represents a fundamental shift from the traditional youth work model toward evidence-based, outcome-focused interventions that deliver measurable improvements in health and wellbeing.

The Council is currently developing proposals to use at least £500,000 of public health grant funding to reinvigorate youth services by significantly investing in youth workers. This targeted investment will be part of a new, multi-agency plan that seeks to improve joint working to help young people thrive, with youth services positioned as a key component of our broader public health strategy.

As part of this approach, an initial £200,000 was invested over the summer holiday into 15 organisations across Liverpool, providing additional capacity for detached youth work. The purpose of this first phase was to respond to the urgent and emerging needs of our communities, including the concerning trend of ASB, and the increased prevalence of ketamine use amongst our young people.

Moving forward, we are now looking at different models of recruitment and training to deploy an army of public health youth workers that can respond to need across our city.

Liverpool’s innovative use of public health funding to rebuild youth services represents a pragmatic response to the fiscal constraints imposed by over a decade of austerity while creating a more evidence-based, outcome-focused approach to youth provision. Rather than simply lamenting the cuts to traditional youth services, we are pioneering new models that demonstrate the clear connections between youth work and public health outcomes.

As we continue to develop this approach, we are committed to sharing our learning with other areas and building the evidence base that will support increased investment in youth services as public health interventions. The young people of Liverpool deserve nothing less than our most innovative and effective responses to the challenges they face, and I believe our public health approach to youth services offers real hope for creating the positive change that our communities need.

The choice is clear: we can continue to pay the high costs of reactive interventions after problems have become entrenched, or we can invest in the preventive approaches that keep young people healthy, safe, and thriving. In Liverpool, we have chosen innovation over ideology, evidence over dogma, and hope over despair. Our young people’s futures depend on getting this right.

Leave a comment