In an era where trust in politicians has plummeted to historic lows, with just 9% of the British public now believing politicians tell the truth, every misleading statement further erodes the foundations of our democratic system. While much focus rightly falls on government accountability, the responsibility to maintain public trust extends equally to opposition parties. Their willingness to distort facts for political gain doesn’t just damage their opponents – it damages democracy itself.

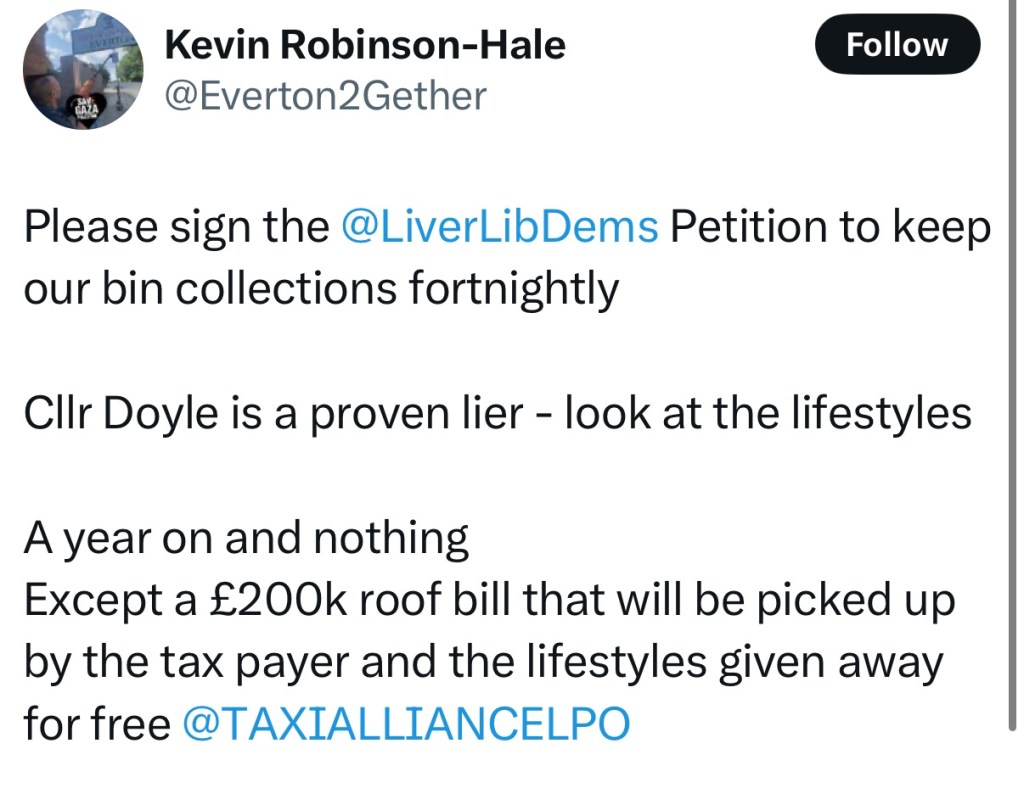

This principle is being tested in Liverpool, where the Liberal Democrats continue campaigning against a fabricated Labour policy that simply doesn’t exist. The Lib Dems have built an entire political narrative around the claim that Labour wants three-weekly bin collections, complete with petitions, press releases, and social media campaigns. Yet this supposed “Labour policy” has never been discussed or considered by Liverpool’s Labour leadership. It is, quite literally, fake news.

The Liberal Democrats’ misleading campaign stems from comments by a single Labour backbench councillor, Steve Munby, who suggested three-weekly collections might be worth considering. Munby, who hasn’t held a cabinet position since 2017, was expressing a personal view – not announcing Labour policy. The distinction is crucial, yet the Lib Dems have deliberately conflated one councillor’s musings with official policy.

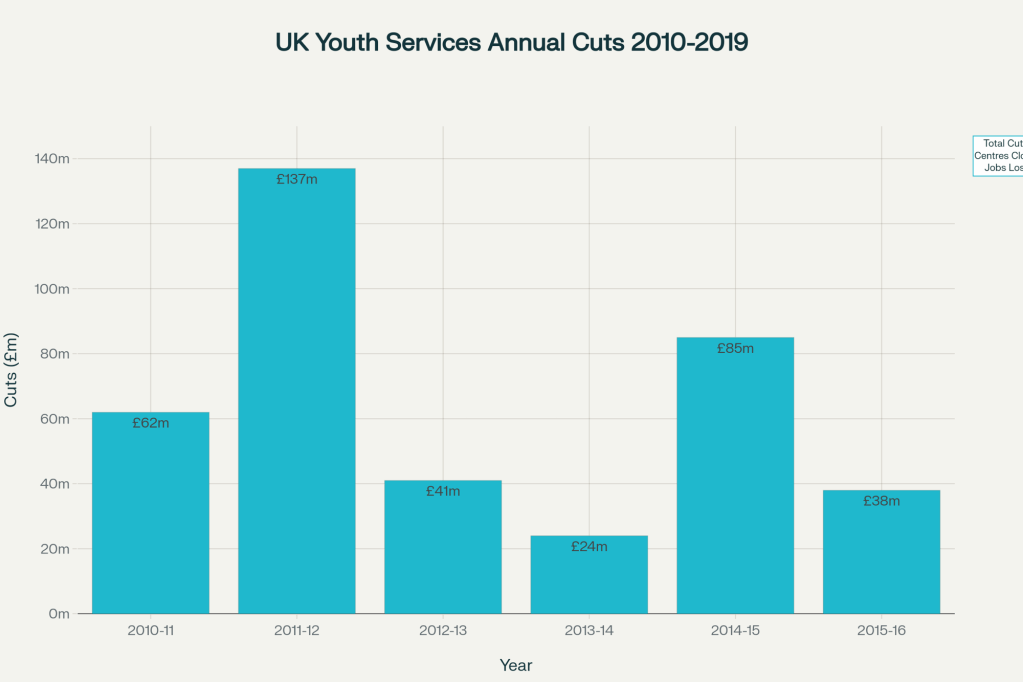

Rather than engaging with Liverpool’s actual waste strategy – improving recycling rates from a dismal 17.9% and introducing weekly food waste collections – the Lib Dems have chosen to campaign against a policy that doesn’t exist. They’ve created their own reality, then demanded residents fight against it.

Opposition parties perform a vital constitutional function: scrutinising policy, holding those in power accountable, and providing alternative visions. However, with this privileged position comes profound responsibility. Opposition parties have a duty not just to oppose, but to oppose truthfully.

When opposition parties abandon truth for convenience, they undermine credibility – not just their own, but that of the entire political system. Research shows that political misinformation creates “an ouroboros of democratic decay,” where false information breeds distrust, making people more susceptible to further misinformation.

The Liverpool controversy illustrates misinformation’s broader democratic impact. The Lib Dems’ false narrative doesn’t just harm Labour – it harms all politicians by reinforcing perceptions that political discourse is unreliable and self-serving.

Research shows that exposure to political falsehoods reduces trust in institutions across party lines. When voters encounter misleading claims from any party, it reinforces cynical assumptions about all politicians. The damage spreads throughout the democratic ecosystem.

Democratic opposition requires the moral obligation to criticise honestly. Opposition parties receive public funding and media coverage because their role is essential to governance. With these privileges comes responsibility for good-faith engagement with factual reality.

The Liberal Democrats’ Liverpool campaign fails this test. Rather than engaging with Labour’s actual waste policies – offering legitimate grounds for debate about costs, environmental impact, and effectiveness – they’ve chosen to tilt at windmills of their own creation.

The Liverpool bin collection controversy may seem like minor local politics, but it represents something serious: the normalisation of deliberately misleading political discourse. Each convenient fiction over inconvenient truth makes the next deception easier to justify and harder for voters to identify.

The Liberal Democrats in Liverpool, like all opposition parties, have every right to scrutinise, even criticise, Labour’s policies. They have the responsibility to do so truthfully. Until they recognise this distinction, they remain part of democracy’s problem rather than its solution.