As a resident and Councillor representing Dovecot, I have watched with growing concern as dozens of England flags have appeared across our community and throughout Liverpool in recent weeks. While I am proud to see our national symbols displayed, I am deeply troubled by the motivations behind this latest surge of flag-flying—motivations that have nothing to do with genuine patriotism and everything to do with exclusion, division, and thinly-veiled racism.

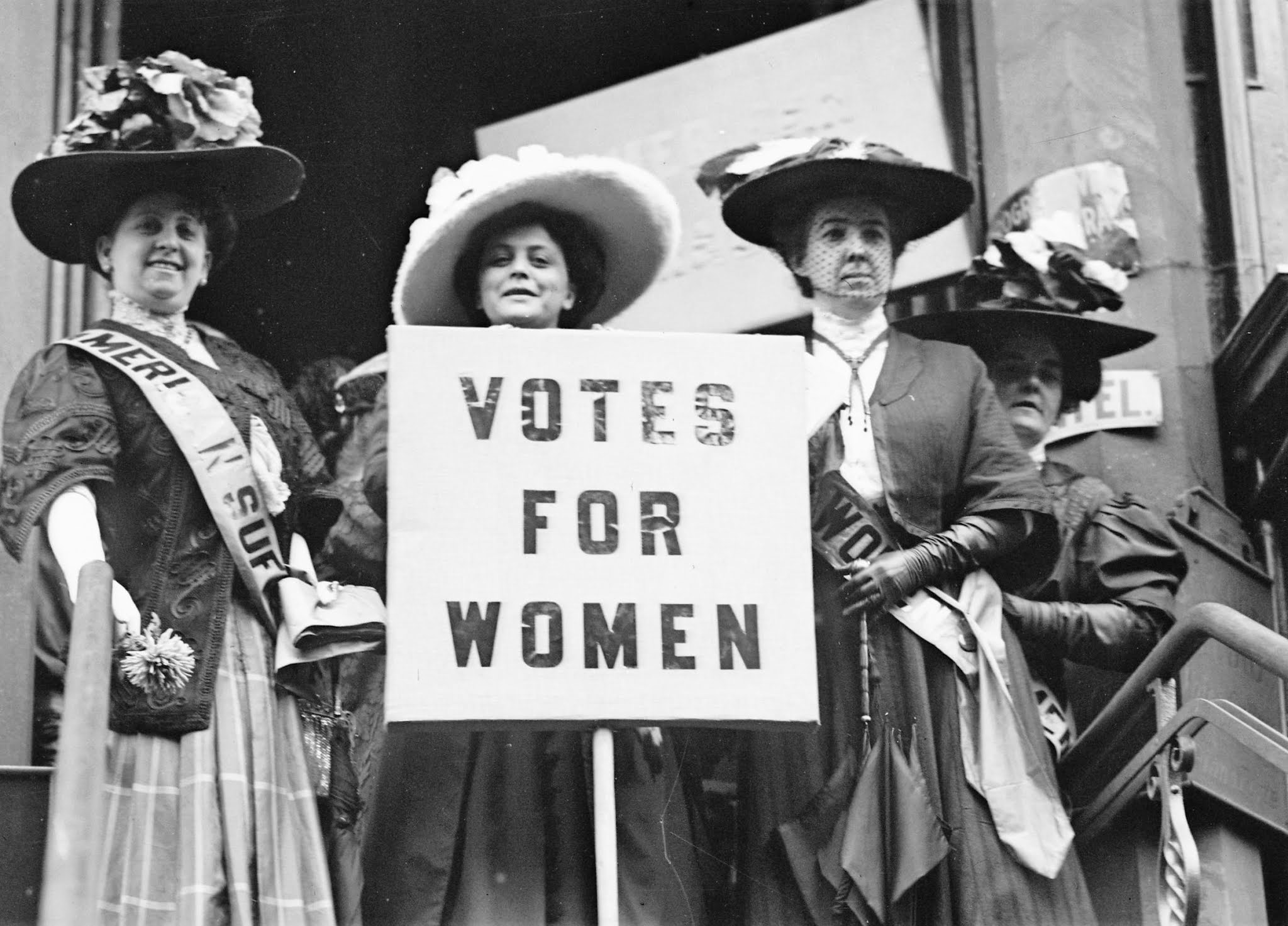

I am proud of the British and English flags, but not for the reasons that drive today’s “Operation Raise the Colours” campaign. I’m proud because these flags can represent the remarkable progress our nation has made toward equality, justice, and inclusion. When I see our flag, I think of the journey we’ve traveled as a society—from the decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967 to the legalisation of same-sex marriage in 2014. I think of women gaining the right to vote in 1918 and 1928, the Equal Pay Act of 1970, and the Sex Discrimination Act of 1975. I think of the England Lionesses winning Euro 2022 and defending their title in 2025, making history as the first English team to win a major trophy on foreign soil.

This is the patriotism I embrace—a progressive patriotism that celebrates how far we’ve come and pushes us toward an even more inclusive future. Our flag, at its best, represents not a return to some imagined golden age, but the ongoing fight for equality and human dignity that has defined Britain’s greatest moments.

The recent proliferation of flags across England, including here in Liverpool and Dovecot, tells a very different story. This campaign, explicitly linked to far-right groups like Britain First and supported by figures like Tommy Robinson, is not about celebrating Britain’s achievements. It’s about sending a message to immigrant communities that they don’t belong.

The timing is telling. Where were these flags when the England women’s team made history? Where was this passionate display of patriotism when the Lionesses were bringing home European championships and inspiring a generation of young girls? The silence then compared to the fervor now reveals the true nature of this campaign—it’s not about pride in our country’s accomplishments, but about exclusion and division.

Political theorist John Denham distinguishes between progressive patriotism and regressive nationalism. Progressive patriotism “defines the national interest as the common good” and is “inclusive, seeking fairness, prosperity and security for all”. It’s “radical because it has no hesitation in calling out the powerful who work against the nation as unpatriotic (even when they wrap themselves in the union flag)”.

Regressive nationalism, by contrast, “seeks to preserve or re-establish the sense of national pride of a previous age” and often engages in “scapegoating and blame-shifting”. This perfectly describes what we’re seeing with “Operation Raise the Colours”—an attempt to use our national symbols to exclude rather than include, to divide rather than unite.

The tragedy is that this exclusionary use of our flag makes many people—particularly young people, ethnic minorities, and those who support multiculturalism—feel uncomfortable with displays of national symbols. A 2024 YouGov survey found that 27% of Britons had an unfavorable opinion of people flying the England flag outside their home, with the divide falling largely along political lines.

This is precisely what the far right wants—to make progressive Britons ashamed of their own flag, leaving the field clear for their exclusionary interpretation of what Britain should be. We cannot allow this to happen.

Our greatest national achievements have come when we’ve embraced change and progress, not when we’ve retreated into exclusion. The abolition of slavery, women’s suffrage, the creation of the NHS, the decriminalisation of homosexuality, marriage equality—these represent the Britain I’m proud of. These are the values our flag should represent.

The recent flag displays across England reveal a fundamental choice about what kind of country we want to be. Do we want to be a nation that uses its symbols to exclude and intimidate? Or do we want to be a country where our flag represents everything we have achieved and still aim to achieve?

I choose the latter. I’m proud of the British and English flags because they can represent our progress—LGBT rights, women’s equality, multiculturalism, and the countless quiet acts of decency and solidarity that define our communities at their best.

But I’m not proud of flags flown to send messages of exclusion and fear. That’s not patriotism—it’s nationalism at its most toxic. And it has no place in the inclusive, progressive, and genuinely patriotic Britain that I believe in and will continue to fight for.

The flag belongs to all of us. It’s time we took it back.